Verrucariaceae

Cecile Gueidan

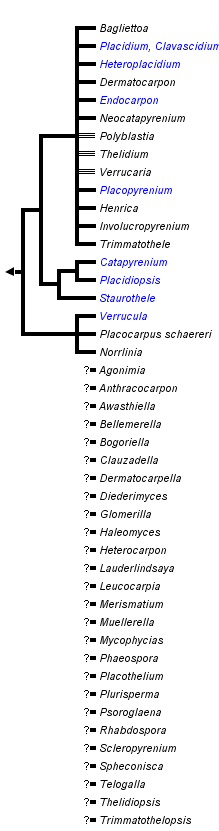

This tree diagram shows the relationships between several groups of organisms.

The root of the current tree connects the organisms featured in this tree to their containing group and the rest of the Tree of Life. The basal branching point in the tree represents the ancestor of the other groups in the tree. This ancestor diversified over time into several descendent subgroups, which are represented as internal nodes and terminal taxa to the right.

You can click on the root to travel down the Tree of Life all the way to the root of all Life, and you can click on the names of descendent subgroups to travel up the Tree of Life all the way to individual species.

For more information on ToL tree formatting, please see Interpreting the Tree or Classification. To learn more about phylogenetic trees, please visit our Phylogenetic Biology pages.

close boxIntroduction

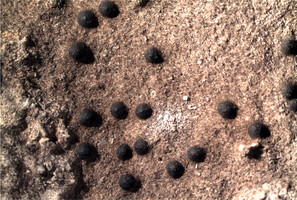

Verrucariaceae are a group of mainly lichenized ascomycetes comprising a large diversity in habits. The structure of the thallus varies greatly in this family, with sizes ranging from a few millimeters to more than ten centimeters in diameter, and shapes from granulose or crustose for the smallest thalli, to squamulose or foliose umbilicate for the largest ones. Species of Verrucariaceae grow mainly on rocks, either epilithically or endolithically within the superficial layer of the rock. Members of this family can also colonize other types of substrates: soils, wood or bark, mosses, and other lichens. Saxicolous species of this family grow mostly in dry environments, but some species are also found in aquatic habitats, such as boulders located in rivers, or marine intertidal and supralittoral zones of rocky shores. Although saxicolous members of the Verrucariaceae are particularly diverse on calcareous substrates, they can also colonize siliceous rocks, especially in aquatic or semi-aquatic conditions. This family occurs worldwide, from the Poles to the Tropics, and includes 46 genera and about 740 species.

Characteristics

Although quite variable in their thallus structure, members of the Verrucariaceae are easy to recognize since their ascomata present good diagnostic features for the order and the family. The perithecial ascomata are characterized by the presence of an apical ostiole and of short pseudoparaphyses (or periphysoids) bordering the upper part of the perithecial cavity and hanging into this cavity without or only barely reaching the hymenium (Janex-Favre 1971, 1975). Asci are typically bitunicate, and their dehiscence was shown in some species to occur by a gelification of the apical part of the outer wall (Grube 1999). The lack, at least at maturity, of long interascal sterile hyphae – which separate them from the Adelococcaceae, the other family of Verrucariales, in which interascal sterile hyphae are persistent (Matzer & Hafellner 1990, Treibel 1993) –, and the positive reaction of the hymenial gel to potassium-iodine are also typical of this family (Henssen & Jahns 1974).

Discussion of Phylogenetic Relationships

Traditionally, three main morphological characters were used to define genera within the family Verrucariaceae (Zahlbruckner, 1903-1908, 1926; Zschacke, 1933-1934): spore septation, thallus structure and the presence or absence of algae in the hymenium. However, this generic delimitation has been considered artificial by many authors (Servít, 1946; Fröberg, 1989; Poelt & Hinteregger, 1993; Nimis, 1993, 1998; Halda, 2003). One of the major issues was the use of spore septation to circumscribe genera within this family. For example, the occasional appearance of longitudinal septa in some spores in specimens with otherwise only transverse septa (pauciseptate muriform spores) led to a great deal of confusion in attributing these specimens to a genus. In some cases, spore septation varies within species and is, therefore, also potentially problematic at the generic level. Similarly, thallus structure and the presence of hymenial algae were believed to be of limited use as synapomorphies, because of possible convergent evolution. Nevertheless, the generic concepts in the Verrucariaceae remained unchanged, with only one attempt (Servít, 1953) to propose a radically different system. Servít (1953) revised the generic classification of the Verrucariaceae mainly based on characters of the involucrellum, but other authors rarely adopted this new system. The scarcity of additional morphological characters available for proposing a new generic system prevented the proposal of important changes in the classification. It is only recently, with the development of molecular techniques, that a new set of data became available for assessing the relevance of morphological characters in classifying species from this family (Gueidan et al. 2007, Savić 2007). Most genera of Verrucariaceae appeared not to be monophyletic, in particular the genus Verrucaria, which was shown to be highly polyphyletic. The main problem in classifying genera in Verrucariaceae was that character states used for delimitation were either plesiomorphic (e.g., the crustose thallus and the simple spore of Verrucaria), or homoplastic (e.g., the presence of hymenial algae). A revision of the generic delineation in Verrucariaceae is now in progress (Gueidan et al. in press).

Altough the phylogenetic relationships between the main genera of Verrucariaceae remained poorly resolved or weakly supported, a few main well-supported groups are worth to notice. The monotypic genus Placocarpus was shown to be sister to Verrucula, a genus including exclusively parasites on species of Caloplaca with anthaquinones. The lichenicolous genus Norrlinia is closely related to these two genera. Epilithic species of Staurothele belong to the same monophyletic group as the two squamulose genera Catapyrenium and Placidiopsis. All the other investigated genera (i.e., Verrucaria, Thelidium, Placidium, Polyblastia, etc...) belong to the same monophyletic group. Among these, the genus Clavascidium was clearly shown to be nested within the squamulose genus Placidium.

References

Fröberg, L. 1989. The Calcicolous Lichens on the Great Alvar of Öland, Sweden. Doctoral Thesis, Institutionen för Systematisk Botanik, Lund. 109 pp.

Grube, M. 1999. Epifluorescence studies of the ascus in Verrucariales (lichenized Ascomycotina). Nova Hedwigia 68: 241-249.

Gueidan, C., Roux, C. & Lutzoni, F. 2007. Using a multigene phylogenetic analysis to assess generic delineation and character evolution in Verrucariaceae (Verrucariales, Ascomycota). Mycol. Res. 111: 1145-1168.

Gueidan C., Savić S., Thüs H., Roux C., Keller C., Tibell L., Prieto M., Heiðmarsson S., Breuss O., Orange A., Fröberg L., Amtoft Wynns A., Navarro-Rosinés P., Krzewicka B., Pykälä J., Lutzoni F. (in press). The main genera of Verrucariaceae (Ascomycota) as supported by recent morphological and molecular studies. Taxon.

Halda, J. 2003. A taxonomic study of the calcicolous endolithic species of the genus Verrucaria (Ascomycotina, Verrucariales) with the lid-like and radiately opening involucrellum. Acta Mus. Richnov., Sect. Nat. 10: 1-148.

Henssen, A. & Jahns, H.M. 1974. Lichenes. Eine Einführung in die Flechtenkunde. Georg Thieme Verlag, Stuttgart.

Janex-Favre, M.C. 1971. Recherches sur l’ontogénie, l’organisation et les asques de quelques pyrénolichens. Rev. Bryol. Lichénol. 37: 421-650.

Janex-Favre, M.C. 1975. L'ontogénie et la structure des périthèces du Staurothele sapaudica (Pyrénolichen, Verrucariacées). Rev. Bryol. Lichénol. 41: 477-494.

Nimis, P.L. 1993. The Lichens of Italy. Museo Regionale di Scienze Naturali, Torino.

Nimis, P.L. 1998. A critical appraisal of modern generic concepts in lichenology. Lichenologist 30: 427-438.

Poelt, J. & Hinteregger, E. 1993. Beiträge zur Kenntnis der Flechtenflora des Himalaya. VII. Die Gattungen Caloplaca, Fulgensia und Ioplaca (mit englischem Bestimmungsschlüssel). Bibliotheca Lichenologica 50, J. Cramer, Berlin, Stuttgart.

Savić S. 2007. Phylogeny and taxonomy of Polyblastia and allied taxa (Verrucariaceae). Doctoral thesis, Uppsala University, Uppsala, Sweden.

Servít, M. 1946. The new lichens of the Pyrenocarpae-Group. I. Stud. Bot. Čechoslov. 7: 49-111.

Servít, M. 1953. Species novae Verrucariarum et generum affinium. Rozpr. Českoslov. Akad. Věd. 63: 1-33.

Zahlbruckner, A. 1903-1908. Lichenes, Spezieller Teil. Pp. 49-249 in: Engler, A., Prantl, K. (eds), Die Natürlichen Pflanzenfamilien. Abt. 1, t. 1. Engelmann, Leipzig.

Zahlbruckner, A. 1926. Lichenes, Spezieller Teil. Pp. 61-270 in: Engler, A., Prantl, K. (eds), Die Natürlichen Pflanzenfamilien, band 8, ed. 2. Engelmann, Leipzig.

Zschacke, H. 1933-1934. Epigloeaceae, Verrucariaceae und Dermatocarpaceae. Pp. 44-480 (1933) and 481-695 (1934) in: Zahlbruckner A. (ed.): Dr. L. Rabenhorst’s Kryptogamen-Flora von Deutschland, Österreich und der Schweiz, 2. Aufl., Bd. 9, Abt. 1, Teil 1. Akademische Verlagsanstalt, Leipzig.

Title Illustrations

About This Page

Duke University, Durham, North Carolina, USA

Correspondence regarding this page should be directed to Cecile Gueidan at

Page copyright © 2008

All Rights Reserved.

- First online 29 January 2008

- Content changed 29 January 2008

Citing this page:

Gueidan, Cecile. 2008. Verrucariaceae. Version 29 January 2008 (under construction). http://tolweb.org/Verrucariaceae/110534/2008.01.29 in The Tree of Life Web Project, http://tolweb.org/

Go to quick links

Go to quick search

Go to navigation for this section of the ToL site

Go to detailed links for the ToL site

Go to quick links

Go to quick search

Go to navigation for this section of the ToL site

Go to detailed links for the ToL site